Using reinforcement learning and multi agent modelling to simulate token economies

MythX (previously Mythril) recently made the decision to drop their custom token and move to a stablecoin-based subscription payment system. Bernhard already posted a good overview of the reasoning behind this decision but I’d like to add some background on how we used simulations to help us understand the dynamics of and issues with the token model. By way of disclaimer, I’m an advisor to MythX and co-creator of the Economy.os tool.

In this post I’ll describe some of the simulations that we ran, explaining our methodology, sharing some results and recommendations for anyone who is thinking about adopting a similar utility token model.

Economy.os methodology

I won’t go into full detail on the tech here but I will describe the basic framework and the reasoning behind the approach.

Blockchains and smart contracts enable us to deploy new economic systems and incentive mechanisms with unprecedented ease. Designing these mechanisms is currently a human-intensive cross disciplinary practice involving many fields including economics, game theory and engineering.

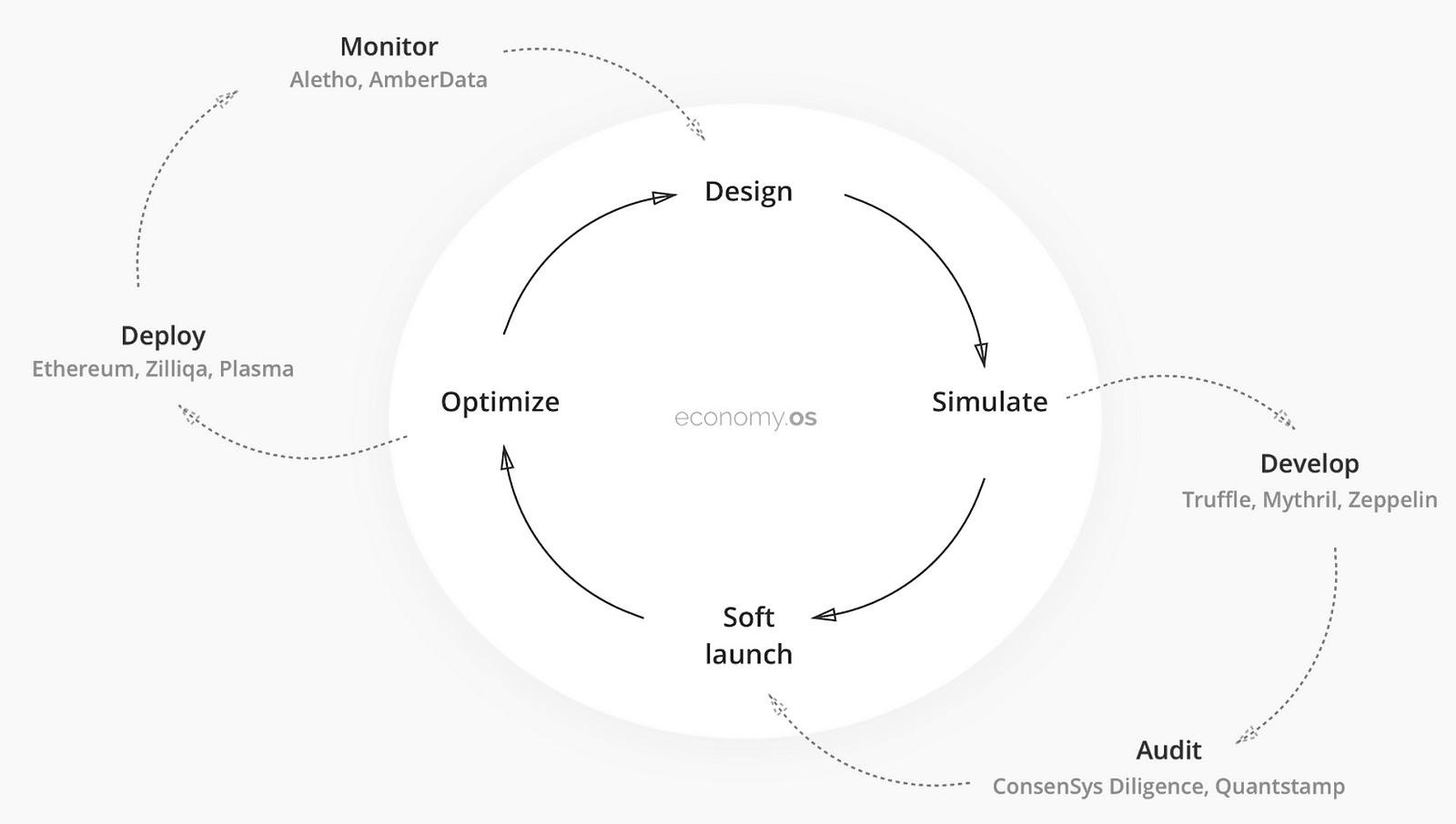

Economy.os is a suite of tools that enable us to design, simulate and optimise economies. We want to enable a more scientific and iterative approach to building decentralized systems, an antidote to the ICO projects of 2017 that proposed a plausible mechanism in a white paper, raised a ton of money, went straight into production and then promptly faced the consequences.

Iterative incentive mechanism design for decentralized economies

Multi-agent simulation

Simulation is the most important component of economy.os. Yes, there is a need for better design tools, but we then need a simulator in order to test those designs. Likewise, there is a need to optimise designs, but we need a simulator as a “runtime environment” for those optimisation problems.

Why do we use agent-based modelling? Human behaviour is non-linear and discontinuous, it can change abruptly at thresholds. It’s generally easier to describe the behaviour of an individual than the dynamics of a whole system. Agent-based modelling allows us to observe global system dynamics based on individual behaviour.

“…economics based on equilibria, local optima and derivatives doesn’t do a good job of capturing how to deal with scenarios where there are multiple equilibria, as well as coordination problems“ — Vitalik Buterin

Our agents fall broadly into two main categories:

- Simple agents — these use simple heuristics or rules to inform their behaviour.

- Smart agents — these use reinforcement learning in order to explore the environment and learn policies for achieving their goals. There is no need for historical data, we can train agents simply by giving them rewards proportional to how well they are meeting their goals. There are many different possible strategies for exploring and learning over time in a non-stationary environment.

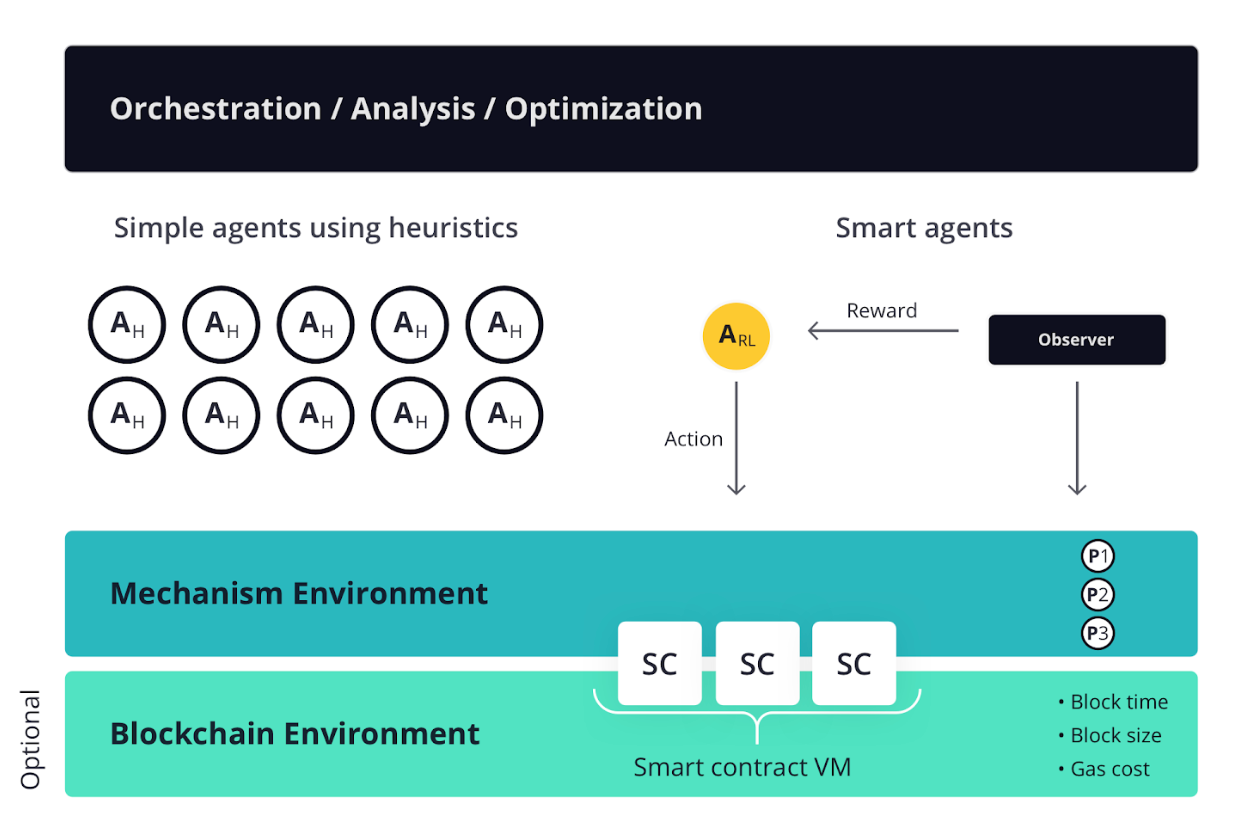

Economy.os simulation architecture

Modelling

The diagram above shows agents interacting with actual smart contracts running on a blockchain. It’s important to note that for the experiments described herein we actually modelled everything in python. Solidity implementations typically require 10–30x more lines of code than a python model so it makes sense to use python for initial modelling and then continue running simulations to verify your solidity implementation.

Why is it important to model the blockchain rather than just the mechanism? Well, all abstractions are leaky. The blockchain (or more generally the execution environment) imposes some constraints that we should consider. E.g. Transaction throughput, transaction cost, block time, miner advantages or collusion. A good example of this is the winner of the FOMO3D game — the game was won by an attack at the blockchain level that the mechanism in the smart contract wasn’t aware of — stuffing blocks with transactions so that other players could not participate.

Another example is front-running on DEXs. It has been estimated that 30% of the transactions broadcast on Ethereum mainnet are arbitrage orders for DEXs. This results in an all-pay auction for gas as bots compete to get their transaction prioritised into the next block. The real mechanism is far more complex than the code in the smart contract would suggest.

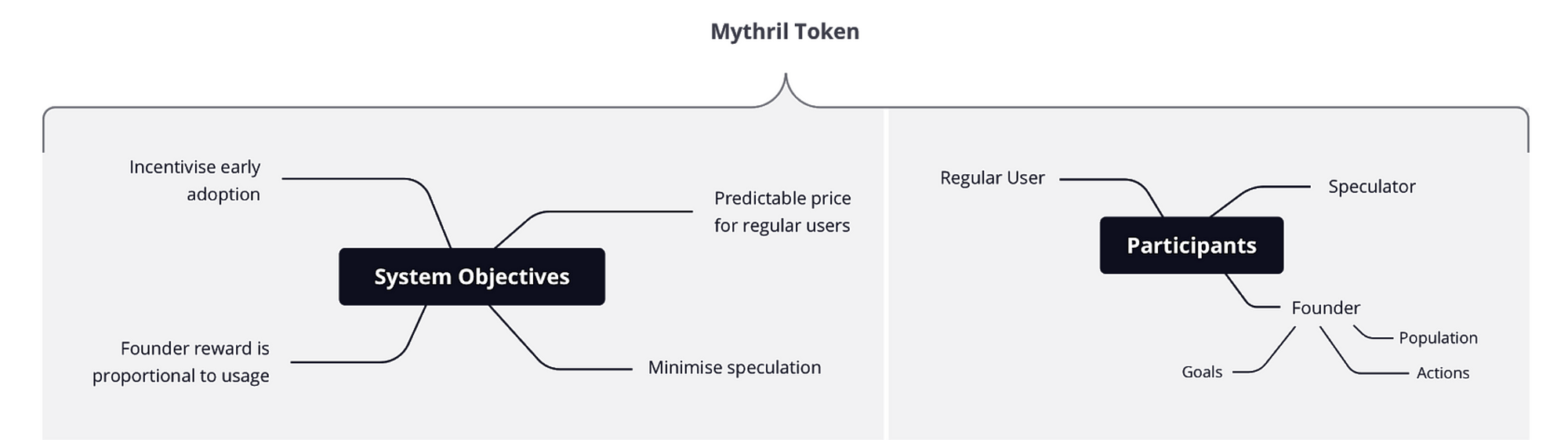

MythX Token Modelling

Before proceeding you might want to refresh your memory of the original token model design. The first thing we want to do when analysing a token model is to summarise the system-level objectives, then identify the agent types and their objectives:

Recall that the token can be bought and sold from a smart contract that acts as a market maker. The price is a function of the number of tokens in existence. Specifically the price is calculated based on a piecewise linear bonding curve that we have designed to represent the different phases of the project’s lifecycle.

Simulation Architecture

In the economy.os simulation tool we have the following architecture:

- Experiments are configured by setting up an environment and then placing agents in that environment. Statistics are then collected on the agent state and global environment state over time.

- Environment contains a model of the market contract, this is mostly just a function that the agents can call to buy or sell tokens which calculates the price based on a configurable bonding curve, we also include a gas cost.

- Agents have many different types, each of which models a particular type of participant in the economy — e.g. founders, stakers, daily users. These agents observe the environment and then on each time step they are asked in a random order to choose an action.

Experiment objectives

We set out these objectives for our experiments:

- Understand how the multi-phase bonding curve will behave under a range of different conditions (e.g. number of users, growth rate of users, distribution of user types)

- Help to set appropriate price/supply points for each phase of the curve

- Predict founder revenue and token price given initial conditions and assumptions

- Potentially uncover issues with the model that have not been foreseen

Agent types

We created the following agent types:

- Speculators only care about making profit. They are given a budget when they are initialised and since they use reinforcement learning they first undergo a training phase where they develop a policy based on their observations. A policy is basically a mapping from variables that they observe (token price, number/proportion of tokens they are holding) to a discretised set of actions (buy or sell some number of tokens). There are many possible ways to tune the training phase that can be configured, including the agent’s learning rate when winning/losing, how much exploration / exploitation they do, and how much they discount future rewards.

- Regular users are simple in their behaviour, they buy tokens and then exchange them for usage. This means that their tokens are handed over to the service provider agent as soon as they are used. There are three subtypes of these agents, representing the three price plans that they will be subscribed to (daily, monthly, annual) and therefore the number of tokens that they buy and the intervals at which they buy them. We also model a linear growth rate of their population.

- Service provider is a special type of agent that receives the used tokens and then sells some proportion back to the market in order to make revenue. In the examples that we show below the service provider will sell 50% of the tokens that they have received every 7 days.

- Stakers are partners and long term holders of the token that can enter the market in the second phase. They simply hold their tokens in this model, taking tokens out of circulation.

- Founder buys all tokens in the first phase of the market, then sells them based on a vesting schedule and heuristic in order to avoid causing volatility in the token price. We tried a few models but the one we’ll use here is where the founder has a vesting schedule with quarterly cliffs that dictates the maximum possible number of tokens they can sell, on each time step they check first whether the token price is above some threshold and if so they calculate the simple moving average over the last 30 days and then sell tokens up to the level that they will move the price to a maximum of some configurable std. deviation from the SMA.

Configuration

Before we look at some results from a simulation let’s set up the basic configuration in a json file. Most of the important parameters here should be explained above, it’s worth noting the “ticks_in_hour” parameter of the environment that is used to do time scaling. In order to interpret the following charts it’s helpful to know that 1 tick represents 1 hour, so there are 8760 ticks per year.

Results

Let’s take a look at some results from running the simulation described in the above config file. This uses the bonding curve shape as defined in the original whitepaper, with very conservatively estimated user numbers across all plans.

These are the headline global environment stats that we care about — the token price, supply and the total population of agents of all types. We can see that the price and supply are clearly related. The jagged pattern is due to the the service provider selling tokens periodically once the price crosses a threshold.

On the first timestep the founder agent buys up all the phase 1 token supply, then within the first day all the phase 2 token supply is bought up by the stakers. These are the only actions that we explicitly force agents to take, for the rest of the time they choose an action based on the state of the environment at that time step.

The price here is shown in USD at a fixed ETH/USD exchange rate — more on that later. The price moves up to $1 (the starting price for phase 3 of the bonding curve) and it oscillates around this point due primarily to buying pressure from the “regular user” agents and selling pressure from “founder” and “service provider” agents.

In order to understand the dynamics of the system we can look at some stats aggregated on each agent type. Note that we’ve removed the speculator agent type here in order to clarify how the other agent types interact.

Service provider revenue vs founder reward

The two main agent types that will be selling tokens will be founders, who bought 2M tokens in phase 1, and the service providers, who receive the spent tokens from the regular users in phase 3.

Let’s take a look at the income that’s generated by both these agent types selling their tokens in the same simulation as defined above.

By the end of the simulation (approx 3.5 years) the service providers have made about $4.3M and the founders have made about $1.6M. Let’s take a look at the number of tokens being sold by founders over this time.

We can see that the founders have sold 1.6M of 2M total tokens allocated to them by time step 30,000, which is about 3.5 years.

Monetary policy

The token is created primarily based on demand for the service it is used to pay for, and then it is sold back to the market by the service providers. In the above charts the service provider is acting on a simple rule of holding the tokens until the price is above $1.05 and then selling 10% of the tokens they are holding.

As we can see from the first set of charts, the service provider can effectively hold the price at a certain level by controlling the selling of spent tokens back to the market by the service provider. If service providers adopt periodic revenue taking (selling) behaviour then we risk producing a predictable environment that speculators can easily benefit from. We might want to also ask what mechanisms we could use to enforce a policy for controlling token supply and therefore price.

One option is for some percentage of tokens to be “burned” when they are spent, so that the service provider can only sell the remainder back to the market. These tokens could be burned in the smart contract that the regular users send their tokens to in order to use the service or we could consider an alternative where there is a bid/ask spread introduced at the market. When tokens are burned it effectively lifts up the price curve.

We have a few options here but all beg the question — what do we want the price to be?

Power of the stakers

Let’s take a look at a chart showing the percentage of tokens held over time for the agent types that will be holding the vast majority of tokens — stakers and founders. Note that as above service providers are selling the tokens they collect back to the market almost immediately hence they do not appear here.

We can see that within this scenario the founders are reducing the percentage of token supply that they own while the stakers maintain a fairly constant percentage. This represents a risk that those early adopters who are currently holding a large percentage of the token supply could collude to dump their tokens on the market and crash the price. We propose considering the following options for addressing this risk:

- Reduce the number of tokens allocated to phase 2.

- Use whitelisting and limit the number of tokens that each user can buy in phase 2, this will not solve the problem but may alleviate it.

- Apply vesting to the tokens that are sold in phase 2.

- Adopt a monetary policy that takes a percentage of tokens out of the circulating supply (as described above) so that the percentage of total tokens owned by early adopters decreases over time.

Speculation

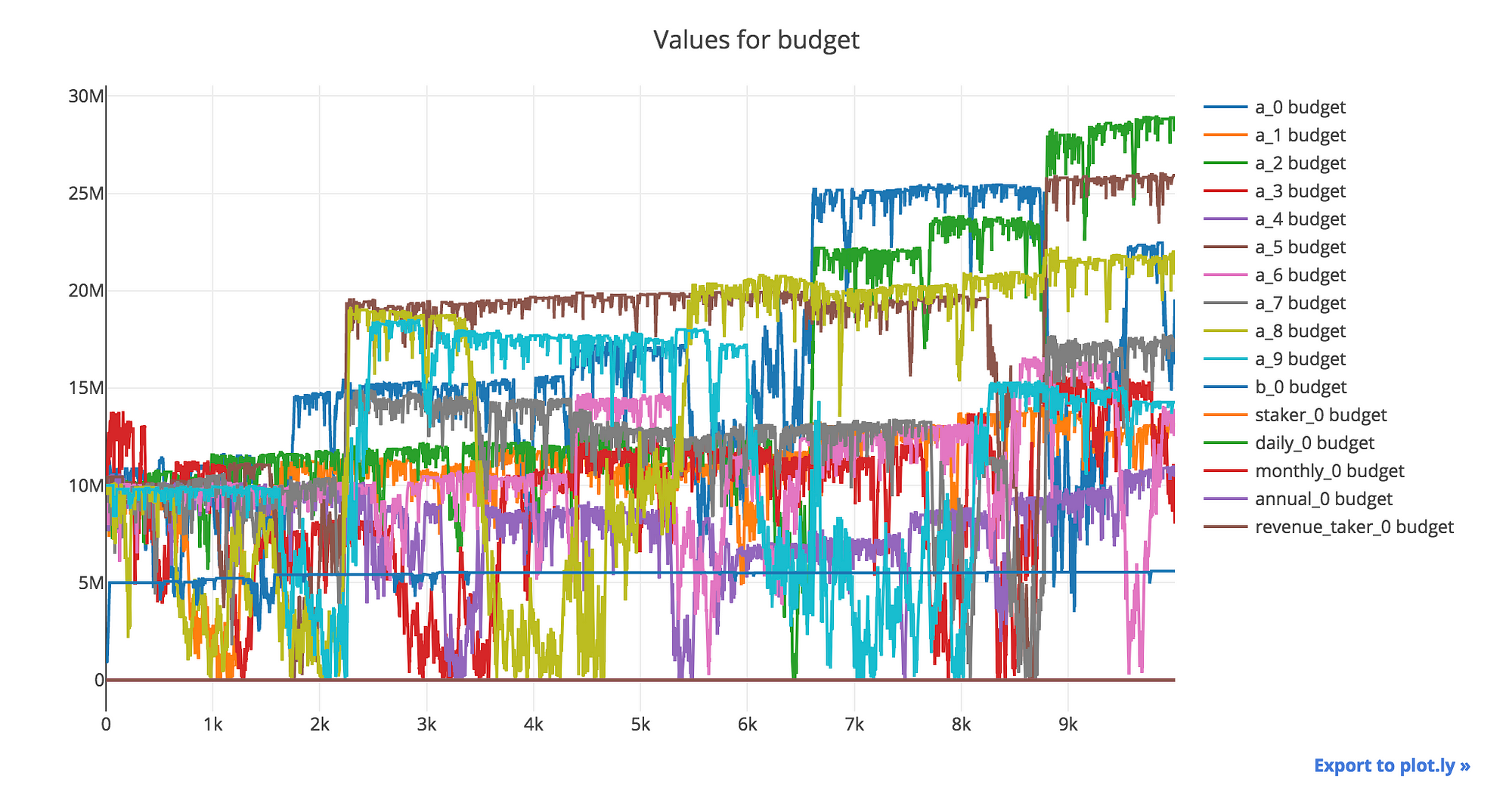

We didn’t get to do extensive research into speculator behaviour but from our work we can see that it is relatively easy for speculators to make a consistent profit in phase two where the gradient of the bonding curve is steep. The following chart shows what happens when we introduce 10 speculator agents in an environment that models phase two of the bonding curve.

Each agent starts out with $10M and by the end almost all have made a profit. N.B. the number of time steps is not significant and when we reduce the gradient of the bonding curve and introduce a small amount of noise we find that the speculators, using the same learning algorithm but trained on the new environment, are unable to make a consistent profit and generally lose money. Ultimately a speculator needs a somewhat predictable environment in order to make predictable profits.

Another potential approach for speculators to game the system would be to watch for transactions being submitted to the mempool and front-run them by submitting their own transaction with a higher gas value. Since the price movement of the token due to a buy/sell order is entirely predictable it would be trivial to execute this attack in a relatively liquid market.

Aside from using ZK-S[N|T]ARKS to hide the nature of the transaction before it is executed, one way of addressing this attack vector is to introduce a bid/ask spread, increasing the market risk that the speculator would have to take.

Ether Volatility

One issue that cannot be studied in simulations but has been on all our minds is the price volatility in ether, which is used as the reserve currency for the market.

The action we propose to address this risk is to use a stablecoin as the reserve currency, most likely Maker DAI. The end user can still use ether (or indeed any currency) to pay for their MythX tokens but their payment currency will be instantly exchanged for the reserve currency (e.g. DAI) which will be stored in the market contract.

Conclusion

There are a number of issues and risks presented here with the token model, most have corresponding solutions or approaches to mitigation but ultimately we decided that the complexity of having a custom token was not worth it and that a more traditional SaaS model was better suited in our case.

The one issue that is completely out of our control is the price volatility of ether relative to fiat currency; the price of ether has fallen by about 10x relative to USD in the last year. While many of MythX’s clients are capitalised with ether they still want price stability in fiat and so for anyone considering using a similar token model we strongly recommend using a stablecoin as your reserve currency. The key drawback to dropping the custom token is that we cannot pre-mint the token at a lower price and use it to reward founders and early adopters.

Another key reason for our decision that we haven’t touched on so far is usability. We designed and built a relatively simple dapp that enables you to manage your MythX account, choose a plan and pay with ether, automatically purchasing the required amount of tokens behind the scenes. While this works well, it’s always going to be simpler for the user to just purchase a plan priced in USD and make recurring payments as they would do for any SaaS software. Given the current low levels of adoption of blockchain technology we feel that prioritising usability and making it as simple as possible to onboard new users is paramount.

In order to implement subscription payments we plan to use the EIP 1337 protocol and reuse most of the subscription management and licensing system that’s already been built. Payments will be in Maker DAI initially but we plan to support more payment currencies over time. This approach enables us to continue to offer transparent revenue sharing with partners, but instead of receiving the custom token they will receive DAI.

I’ll finish by quoting from Bernhard’s post on the subject, laying out the three main benefits that we’ve realised by taking this approach to payments over using a more traditional credit-card based system like Stripe:

- Anyone with an Internet connection can participate in our security tools market even without a bank account.

- No value is extracted from our economy by credit card processors and banks.

- Revenue sharing can be implemented in a transparent (and eventually fully decentralized) fashion.